Reading fiction has always been a double-edged sword for me. Some of the most intimate moments I’ve spent alone is while reading fictional stories, while at the same time, feeling a pang of disappointment for myself because I wasn’t doing anything “productive.” Is this mere entertainment? Am I just escaping my real-life responsibilities and reading stories of make-believe? While I still haven’t found sincere answers to these questions, I’ve grown more confident of what I enjoy and what I don’t, which has consequently helped me find peace with this conflict. Over the years, I’ve realized that reading good literature is therapeutic for me - not to be used as an afterthought but essential to keep me functional.

Stoner was another great session in my therapy.

A story that on the surface feels depressing and sad, but curiously enough has immense hopeful undertones. This is the ordinary story of a man whose only goals in life are to attain two of the most notoriously difficult things known to mankind - knowledge, and love. He fails in both, but if you look underneath the surface, he succeeds in attaining both as well - just enough to make him feel satisfied but not enough to make the world think the same. The story is simple. A man hailing from rural American farmland attends university, falls in love with literature, and decides to dedicate himself to fulfill his passion. He starts teaching at the university, gets married by following his desire, but without falling in love, has a passionate love affair and, in the end, dies without having accomplished much.

But the way Mr. Williams writes this simple story is mesmerizing, to say the least. There’s an existential dread in all the interactions, always pulsing with energy, and the prose flows with a perfection, almost to a fault. When I looked back at the book having finished my 4-hour marathon run through it, I noticed that for the first 100 pages or so, the book had a lot of markings - sentences I had loved, descriptions I had enjoyed - however as it moved further, I got tired of doing so, simply because it only got better and better. If I had continued, the whole book would have been messed up by my pencil.

Throughout the book, I could sense Camus’s influence on his writing; the existential dread always present. All the characters felt as if they could easily exist in my universe. The slow torment that the protagonist went through, at times, felt too personal, as if someone had mercilessly ripped out a few chapters from my life and laid it bare for the world to see. One of these moving passages is written at approximately two-third of the book, which I can’t help but quote below:

In his extreme youth, Stoner had thought of love as an absolute state of being to which, if one were lucky, one might find access; in his maturity, he had decided it was the heaven of a false religion, toward which he ought to gaze with an amused disbelief, a gently familiar contempt, and an embarrassed nostalgia. Now in his middle age he began to know that it was neither a state of grace nor an illusion; he saw it as a human act of becoming, a condition that was invented and modified moment by moment and day by day, by the will and the intelligence and the heart.

To illustrate an example of the existential feelings at play in the novel, here’s another passage where Stoner wonders about the futility of knowledge at a tumultuous point in his life:

He had come to that moment in his age when there occurred to him, with increasing intensity, a question of such overwhelming simplicity that he had no means to face it. He found himself wondering if his life were worth the living; if it had ever been. It was a question, he suspected, that came to all men at one time or another; he wondered if it came to them with such impersonal force as it came to him. The question brought with it a sadness, but it was a general sadness which (he thought) had little to do with himself or with his particular fate; he was not even sure that the question sprang from the most immediate and obvious causes, from what his own life had become. It came, he believed, from the accretion of his years, from the density of accident and circumstance, and from what he had come to understand of them. He took a grim and ironic pleasure from the possibility that what little learning he had managed to acquire had led him to this knowledge; that in the long run all things, even the learning that let him know this, were futile and empty, and at last diminished into a nothingness they did not alter.

I should stop lest I give myself a free rein and quote the entire book itself. And so I shall stop here. Pick this book up from dusty old shelves of second-hand bookshops and pass it onto others with a note saying, “Thank you for accepting this gift. Thank you for existing.” Maybe someday somewhere, this gift would end up saving someone.

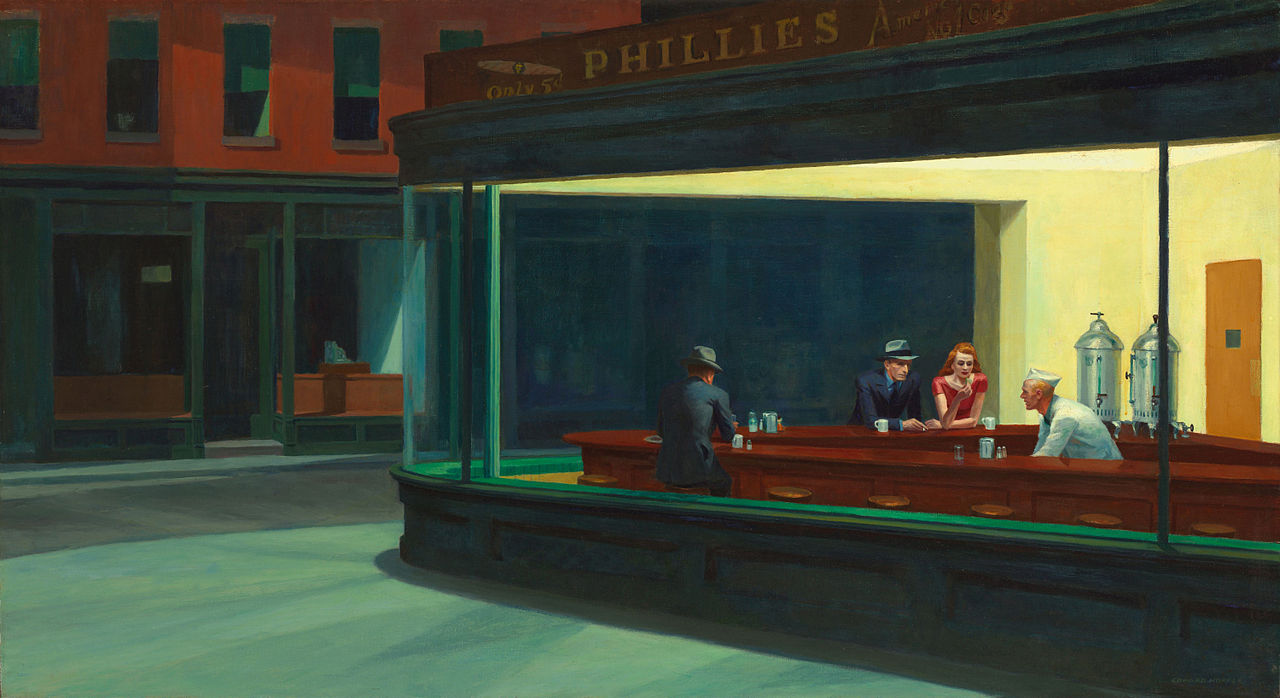

P.S: If one picture could summarise this whole book for me, it would be the famous oil painting by Edward Hopper, named Nighthawks.